I walked down Berlin’s Georgenstraße many times when I lived in the city; usually on bitterly cold mornings while making my way from Friedrichstraße station to the labyrinthine Staatsbibliothek building on the Unter den Linden. It was not until sometime later that I became aware of the fact that, on this reasonably quiet side street in the centre of town, under the shadow of the elevated Stadtbahn railway, stood the ghost of one of Berlin’s forgotten museums, the Museum für Meereskunde (Museum of Marine Science).

The museum was created by the Berlin Institute for Marine Science (Institut für Meereskunde), itself founded as part of the University of Berlin in 1900. Heavily funded by the Prussian Crown, the principal aim of the museum was to instil in Berliners a sense that ‘the ocean was part of their German identity’. Given Germany’s unfavourable coast-to-land-area ratio, particularly compared to its chief European rivals Britain and France, there was much that the museum was required to do.1

The result was a succession of rooms and displays that covered all things marine: Germany’s naval history, natural history, science, navigation, exploration, commerce, and fishing methods. The museum, which opened in 1906 under the directorship of the geographer Albrecht Penck, proved popular with Berliners, and quickly became one of the most visited collections in the city. In 1913 the museum grew in size when it acquired a number of adjoining rooms that formerly belonged to the university library on Dorotheenstraße.2

The underlying substance of the museum—amid the glasses cases of stuffed birds, dioramas of Antarctic landscapes, cutaway sections of ships and polished brass navigational instruments—was that of an important imperial project; a showcase of Germany’s global achievements and ambitions, which were reliant on the nation being a first-class sea power.

For example, Germany’s commercial importance was demonstrated by a model of that part of Hamburg’s docks in which vessels on the Hamburg-America Line loaded and unloaded their goods. At the end of the nineteenth century, the Port of Hamburg was one of the largest in the world, and the Hamburg-America Line the largest shipping company in the world. Hamburg was indisputably Central Europe’s primary hub for transatlantic freight and passenger transport.3

Elsewhere in the museum, Germany’s imperial credentials were underlined by displays depicting scenes and artefacts from the its colonial possessions. In one room stood a model of a cliff wall, crowded with guillemots from the North Sea island of Helgoland, only recently handed over to Germany by Britain with the signing of the Helgoland-Zanzibar Treaty in 1890.

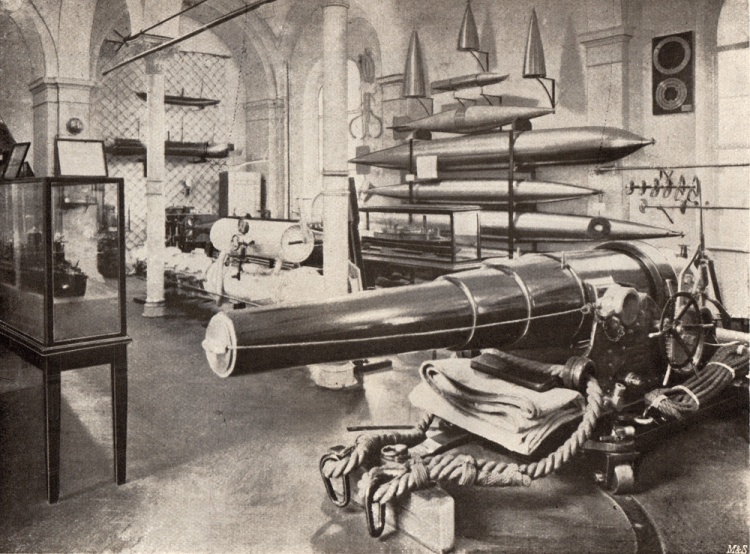

Elsewhere, the focus was very much on Germany’s technological efforts and achievements in building an imperial navy, with mounted guns and torpedoes, models of the latest battleship classes, and military insignia proliferating throughout the museum. In the museum’s atrium stood a reconstruction of the bridge of the Braunschweig, one of the German Imperial Navy’s newest battleships, commissioned in 1904.

In the museum courtyard stood the twenty-six-foot-long Brandtaucher, Germany’s first submarine, built by Wilhelm Bauer in 1850 and intended for use against the Danish blockade of Kiel in the war between the two countries over Schleswig-Holstein. Bauer’s submarine sank in the harbour at Kiel in February 1851, and remained underwater for over thirty years, before it was salvaged in 1887.4

With such a heavy focus on exhibits from the imperial naval collection, and scenes and artefacts from Germany’s colonial possessions, the main aim of the Museum für Meereskunde was unquestionably the promotion of Germany’s Empire. Unsurprisingly, its opening on 5 March 1906 featured plenty of imperial pomp, with Kaiser Wilhelm himself in attendance, accompanied by the Prince of Monaco. The museum’s corridors and auditorium were bedecked with flowers, and students in regalia assembled on the stairs and balcony overlooking the auditorium. Amongst the pomp stood senior representatives from the German worlds of science, finance, culture, the Navy and the Government, including Vice Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, Secretary of State for the German Imperial Navy.5

In keeping with the general air of sabre-rattling that could be heard all over Europe at the time, the Berliner Volks-Zeitung reported, on the occasion of the museum’s expansion in 1913, that new exhibits to be displayed included models of the battleship Helgoland and the cruisers Moltke and Magdeburg, and sections of various torpedoes and machine guns.6

Then came the Great War, which ended with the German revolution in late 1918, triggered by a revolt amongst German sailors at Kiel. This was followed, in June 1919, with the scuttling of the German fleet at Scapa Flow, under the orders of Admiral Ludwig von Reuter. But in spite of Germany now having no navy to speak of, and being shorn of much of its colonial possessions, the Museum für Meereskunde survived these traumas. All of which begs the question: what was the museum like, what was its raison d’être, during the years of the Weimar Republic?

A newspaper article from 1925, published to commemorate the twenty-fifth anniversary of the founding of the Institut für Meereskunde, offers some insight into the museum’s status during the Weimar years. The costs of the war and inflationary years, the article conceded, had left no money for acquisitions or research expeditions. The German naval collection remained, but it did so now as a ‘reminder of the mentality of the old regime’, with its ‘tame models’ and ‘pompous paintings of sea battles’.7

The museum had to wait until late 1930 for a significant new exhibit. It came in the form of a presentation dedicated to the work of the German Atlantic expedition, in which the vessel Meteor carried out numerous scientific surveys in the southern Atlantic Ocean between 1925 and 1927. A photograph taken by Willy Römer, now part of the collections of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation (Preußischer Kulturbesitz), shows a scene from the new exhibition celebrating the Meteor’s expedition. Artefacts in the exhibition included a model of the Meteor, a relief map of the south Atlantic ocean, and a range of research apparatus, including a deep-sea thermometer, and depth sounding and water salinity measuring tools.8

In 1935, with the Nazi’s creation of the Wartime Navy (Kriegsmarine), the Museum für Meereskunde revived its sabre-rattling tone. Slideshow presentations were regularly held at the museum, illustrating the evolution of the Germany navy from 1890 to the present day.9 Glass cases displayed flotillas of model warships with miniature Zeppelins flying overhead. One image of an exhibition poster, which clearly attempts to link the seagoing prowess of Germany’s earliest peoples with the present time, declares ‘the development of warships, from the boats of the Teutonic peoples to the dreadnoughts of today’.

The Museum building on Georgenstraße did not survive the raids over Berlin by Allied bombers during the Second World War. Many of its collection items have survived though, and are now held at the Technical Museum and Technical University in Berlin.

Notes

1. Führer durch das Museum für Meereskunde Berlin (Berlin: Institut für Meereskunde, 1913). See also: Lynn K Nyhart, Modern Nature: the Rise of the Biological Perspective in Germany (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009), 278–81.

2. “Das Schiff als Eroberer, Ernährer und Entdecker” Berliner Volks-Zeitung, 24 January 1913 <http://www.theeuropeanlibrary.org/> [accessed 11/05/2016]

3. Edwin J. Clapp, The Port of Hamburg (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1911), 54.

4. Laurence Sondhaus, Naval Warfare 1815–1914 (London, Routledge, 2001), 65.

5. “Die Eröffnung des Museums für Meereskunde” Berliner Volks-Zeitung, 6 March 1906. <http://www.theeuropeanlibrary.org/> [accessed 08/05/2016]

6. “Neuerwerbungen des Museums für Meereskunde” Berliner Volks-Zeitung, 2 September 1913. <http://www.theeuropeanlibrary.org/> [accessed 11/05/2016]

7. “Schiff und Fische” Berlin Volks-Zeitung, 26 April 1925. <http://www.theeuropeanlibrary.org/> [accessed 11/05/2016]

8. “Von der Meerestiefe in die Stratospäre” Berliner Volks-Zeitung, 2 November 1930. <http://www.theeuropeanlibrary.org/> [accessed 11/05/2016]

9. “Die deutsche Kriegsflotte von 1890 bis 1935” Hamburger Nachrichten, 17 October 1935. <http://www.theeuropeanlibrary.org/> [accessed 11/05/2016]