Throughout the summer of 2008 I lived in an apartment block on the corner of Wilhelmstraße and Hannah-Arendt Straße, at the heart of Berlin. On summer evenings I watched the sun set in a pale sky over the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, and finally sink below the trees of the Tiergarten in the far distance.

At the rear of the apartment, the lounge window looked out onto the apartment block’s car park. Nearly every time I looked out of that window my eyes were drawn to a huddle of tourists that stood on the dirt verge between the car park and pavement. There they were, snapping pictures on their cameras and phones, irrespective of time of day or weather, the primary colours of their shorts, t-shirts, cagoules and backpacks standing out in an otherwise concrete grey arena.

I was curious as to the attraction of this unremarkable spot, but not curious enough to go look for myself until some six weeks into my stay, when, early one evening, after the last of the tourist groups had departed, I finally went down to see what all the fuss was about.

My discovery was unexpected and shocking, and I recall clearly how I felt at the time, as I stood, agog, in front a solitary information panel that told me the remains of Hitler’s bunker lay buried in the ground underneath my feet. This was the very spot where the Nazi leader spent the last few weeks of his life, the point onto which the violence of the Battle of Berlin had been focused. As I stood and absorbed the revelation, I felt the quietude that surrounded me, the sheer banality of this space with its parked cars and apartment windows, close in about me. Looking down, I scuffed the ground with my feet, and thought about what other secrets lay beneath the sandy soil of Berlin.

The revelation filled me with a renewed sense of curiosity about the apartment complex in which I was living. I asked my host later that evening, who told me that these blocks were built in the late eighties, just before the Wall came down. Ranged along Wilhelmstraße, they were unlike most of the other residential developments being built at the time in East Berlin, in that they were well-made, well-appointed blocks, with generously proportioned apartments. The East German Government intended them, my host said, to be a gesture of defiance to the West – a statement that everything was fine and dandy in East Germany, in spite of the country being close to the point of collapse.

Source: Bundesarchiv, via Wikipedia.

The residents of these new flats were a mixture of East German Government Nomenklatura, and some of the country’s highest profile sports stars. Many residents had windows that, like mine, looked out to the west. But whereas I looked out across an immaculate, unified landscape, they looked out across the death strip and the Wall, toward the ruined wasteland of Potsdamer Platz.

Then the Wall came down, and everything changed forever.

—

Surrounding each of these apartment blocks, squeezed in between the buildings and the pavement, ran narrow strips of greenery: a mix of lawn and dense, low shrubbery. Nothing unremarkable about that, but I never stopped being surprised at how many rabbits lived amongst those thin slivers of nature. Every evening, as dusk fell, you could guarantee that you would spot one bounding across the street, from one green sanctuary to another. Only in Berlin, I thought, might you find rabbits living wild in the centre of the city.

The close proximity of the Tiergarten is one reason for the presence of so many rabbits, but so is the fact that much of this part of Berlin has never been built upon, in spite of the city first encroaching onto it nearly three centuries ago. Until quite recently, there were plots of land in the surrounding area that had remained untouched since reunification, the most significant being one large tract adjoining Leipziger Straße, formerly home to a cliff face of scaffolding, now transformed into the LP12 Mall. In the Cold War era, the close proximity of the Wall ensured the much of this area remained desolate, a death strip into which only rabbits and angels feared to tread.

Prior to the War, and since the 1730s, when it first came within the bounds of the expanding city, most of this area was occupied by gardens belonging to a row of opulent villas on Wilhelmstraße. These palatial piles formed part of the suburb to the south of the Unter den Linden known as Friedrichstadt. The owners of these villas were prominent figures of the Prussian nobility; families like the von Schwerin of Mecklenburg, the von Schulenburg of the Altmark, the von Pannewitz of Lusatia, and members of the Hohenzollern dynasty.

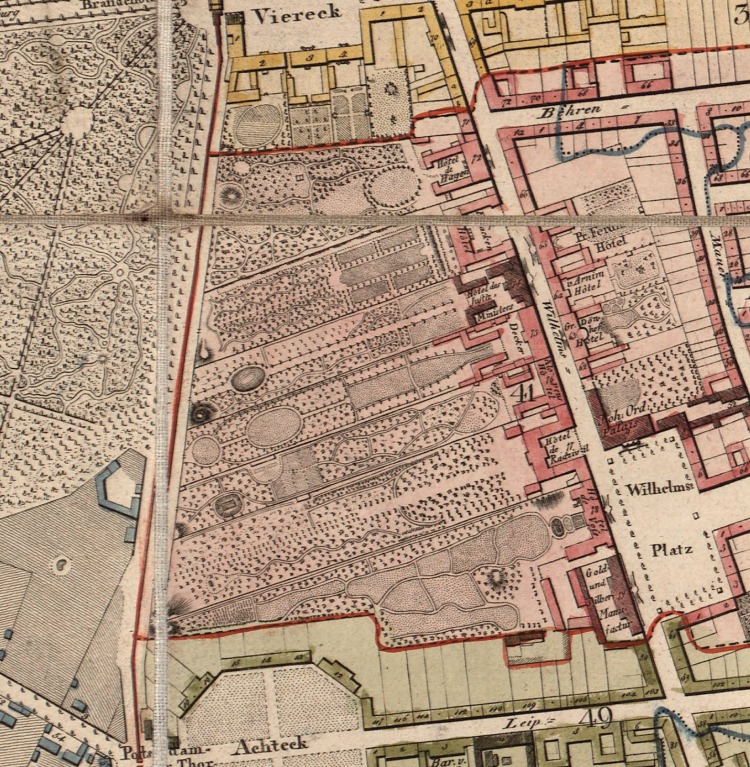

If the villas were big, then the gardens were even bigger, stretching out, in some cases, nearly half a kilometre to the customs wall now marking the limits of the city. Mid-eighteenth-century maps indicate the formal nature of many of the gardens, with their symmetrical, geometric layouts. They show neat paths dividing lawns and flowerbeds into regular rectangles and triangles, interspersed with water features and terraces.

A significant change to the villas along Wilhelmstraße occurred in 1819, when the Prussian Government’s Foreign Ministry took over the villa at no. 76, originally home to the von Pannewitz family. From this moment on, Prussia’s government departments started to slowly coalesce on Wilhelmstraße. By the end of the nineteenth century, Wilhelmstraße had become synonymous with German Government, a literal corridor of power, and home to the Minister for the Royal Household, the Chancellery, the Minister of Finance, the Colonial Office, the Prussian State Ministry, the Ministries of Food and Transport, and the Foreign Office. The apartment block in which I’d lived, on the corner of Wilhelmstraße and Hannah-Arendt Straße, occupied a site that was once home to the Imperial Office for the Interior. Despite their change from aristocratic homes to government offices, the gardens of these villas remained intact, and later became known as the ministerial gardens.

The redevelopment of Wilhelmstraße continued into the Nazi era. New government departments that established themselves on the street in the thirties included the Ministry for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, the Ministry of Aviation, and the SS. Dissatisfied with the existing Reich Chancellery building, Hitler had his favourite architect, Albert Speer, design and build a new Chancellery complex, complete with underground bunkers.

Evidence of the gardens’ appearance in the years before the Second World War can be seen in surviving photographs. In one image, taken in February 1932, German President Paul von Hindenburg walks with his grandchildren in the gardens of the presidential palace on Wilhelmstraße. The group walk along a tree-lined path with the palace behind them, visible through the bare branches of trees. The figures cast their long dark shadows onto a light dusting of snow. Another photograph, taken in 1937, shows the presidential palace gardens from the terrace of the palace. It is a quiet, restful, and luxurious scene, unquestionably a stark contrast to the political and social turmoil taking place in the streets beyond the trees.

Not unsurprisingly, Wilhelmstraße was a key target for the Allied bombing raids that flew over the German capital throughout the Second World War, and bore witness to intense fighting and destruction in the final days of the Battle of Berlin in May 1945. By the end of the War, much of Wilhelmstraße was in ruins, and, tarnished by its association with Prussian and Nazi militarism, remained largely abandoned until the 1980s.

—

After reunification, the area formerly occupied by the ministerial gardens was identified as a key site for redevelopment as part of the German Government’s programme to revitalise the city, and reestablish Berlin as its headquarters. Today, the area is home to the administrative offices of several German regions (Hessen, Lower Saxony, Saarland, Brandenburg, Mecklenburg, Rheinland-Pfalz, and Schleswig-Holstein). The memory of the ministerial gardens has been preserved with the insertion of a new street into the landscape. In der Ministergärten cuts right through the space in which the gardens once existed. On modern street maps, the new streets runs west to east, connecting Ebertstraße to Gertrud-Kolmar-Straße, before curling around in a curious loop that embraces the site of Hitler’s bunker, and terminating as an access road to the apartment block car park.

On those summer evenings back in 2008, I frequently walked along In der Ministergärten as I made my way back to my apartment after a long day spent exploring the city. Occasionally, garden parties would be in full swing in the grounds of the regional administration buildings. From the street I could see very little bar the tops of white marquees, but I could hear music and the gentle hum of voices talking and laughing, of bureaucrats from a unified Germany rubbing shoulders in a space where, going back in time, Hitler plotted his takeover of Europe, Hindenburg walked with his grandchildren on a cold February morning, and the Prussian nobility built palaces for themselves in the shallow Brandenburg sands.

Further Reading

Bezirksamt Mitte von Berlin, Städtebauliche Expertise über die Erhaltung der städtebaulichen Eigenart gem. § 172 Abs. 1, Satz 1, No. 1 BauGB füur die Wilhelmstrasse im Bezirk Mitte von Berlin, Ortsteil Mitte (Berlin: 2016).

David Clay, Berlin (New York, Basic Books, 2000).

Brian Ladd, The Ghosts of Berlin: Confronting German History in the Urban Landscape (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998).

Paul Seabury, The Wilhelmstrasse: A Study of German Diplomats under the Nazi Regime (University of California Press, 1954).